Dive deep into the details to decide on the best blades for dropping gobblers with a vertical bow or crossbow.

Text and photos by Al Raychard

Okay, let’s put the cards on the table first thing. Success in the turkey woods really isn’t that difficult. There are any number of challenges unique to getting the job done and there are times when things don’t go as planned, and times when mistakes and miscalculations are made. But with the necessary preseason homework, getting a shot at a bird isn’t rocket science or brain surgery. The real challenge is making that shot count. This is particularly true with archery gear.

AIM SMALL, MISS SMALL

One of my favorite movies is “The Patriot,” starring Mel Gibson as main character Benjamin Martin, a veteran of the French and Indian War, and a widower raising seven children on his farm during the American Revolution. After his oldest son is taken prisoner by the British and second-oldest son is killed trying to help his brother, Martin takes revenge by ambushing the British unit with two much younger sons, each barely old enough to carry a musket. Just before the British arrive and while setting up the ambush, Martin tells the boys, “Remember what I taught you, aim small, miss small.”

I had never heard the expression before but have since learned it is not uncommon in the shooting sports, especially tactical shooting. There are several ways to interpret it, but essentially it means if I simply aim at a target and miss, I miss the target, but if I aim at a small specific spot on that target and miss that spot, I will still hit the target, most often within an acceptable margin. When hunting, it is the vitals we should always be aiming for, and when it comes to arrowing turkeys in particular, “aim small, miss small” is a philosophy that I keep in mind.

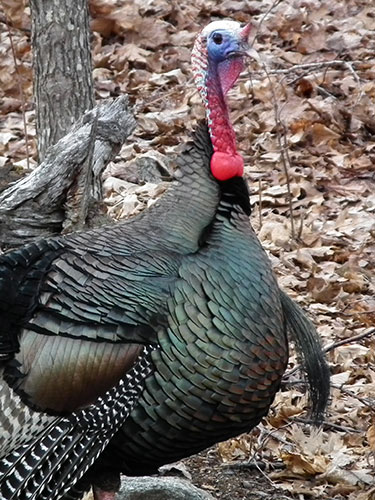

The reason for that is quite simple. In various poses and at various angles turkeys look deceptively large, but behind the wings and beneath all of those feathers is a rather small body. Tucked inside are the turkey’s baseball-size heart and lungs. Due to the deceptive appearance and small vital area, a terminal shot with an arrow is always a challenge. Unlike when bowhunting deer, compounding the challenge is the fact that those vitals are slightly higher than center of mass, which is why a slightly higher-than-center shot on a bird is always better than a lower shot. The vitals also seem to deceptively shift, depending on whether a bird is in full strut, quartering, standing broadside or walking away. The fact that turkeys are always in a state of awareness or perpetual motion only adds to the challenge of terminally sticking one with an arrow.

SELECTING BROADHEADS

Of course, a lot goes into successfully bow-killing a turkey. The proper setup and patience for that ideal shot are but two factors that will make it possible. Once an arrow is underway, broadheads also play a major role. Today’s bowhunters have a choice from a wide array of broadheads and it can get a tad confusing when deciding what are the best for hunting turkeys. This is particularly true when it comes to whether fixed or mechanicals are best, and how large of a cutting diameter is required to get the job done. The final choice, however, isn’t that difficult.

An important thing to keep in mind when selecting broadheads is that turkeys have low body mass and lack heavy muscle and bone structure. There is little need to worry about how much energy and shock is delivered. While pass-through shots are always preferred due to the potential increase in blood loss, shots that fail to pass through can be just as deadly, since the arrow and broadhead continue to cause massive damage as the bird thrashes and flutters about on the ground.

The key to success is shot placement critically crippling the bird, ideally through one or both wings and/or the vitals to prevent the bird from taking flight or running off, or lopping off the head. To do that an arrow has to fly accurately to the target and the broadhead must cut large holes and inflict massive tissue damage and blood loss.

THE QUESTION IS HOW BIG

Due to their feathered covering, turkeys are notoriously bad at dispensing blood once hit with an arrow, so when that happens we need them to go down and stay down. Big holes, the bigger the better, will get the job done. I’ve killed a number of spring and fall birds with the very same 100-grain mechanical, 1⅜-inch diameter broadhead used for deer hunting, largely because I forgot or neglected to change over. And I have no qualms about using them if the conditions are right, which means the bird is providing a satisfactory shot opportunity. If so, I know they fly extremely well, are accurate off of my crossbow out to 40 yards and more. So, I have confidence in them and they cut a decent hole to create considerable internal damage.

But when specifically gearing up for turkeys I prefer something with a slightly larger cutting diameter. The reason for this is because not all bow-shot opportunities at turkeys are ideal and not all bow shots are perfect, despite our best efforts. In addition to making bigger holes and creating more damage, broadheads with larger cutting diameters are more forgiving of misplaced shots and can make marginal shots into killing shots. A slight miss to the vitals with a 1⅜-inch cutting diameter will likely kill a bird, but hitting the same spot with a broadhead providing a larger cutting diameter greatly increases the chances of touching or completely severing the heart or lungs. It is amazing how much damage an extra 1/8 inch to 1/2 inch of cutting can do and the difference it can make.

For the majority of turkey bowhunting situations, broadheads with a 1½-inch diameter are generally considered minimum, those providing a 1¾-inch diameter are better and those providing a 2-inch diameter better still. Of course, that is, if the larger and often heavier broadheads do not negatively influence a bow’s speed and accuracy. With today’s blisteringly fast compound bows and crossbows, the difference should be negligible. But it is always best to find out and make any necessary adjustments before the season opener.

FIXED OR MECHANICAL

There is an ongoing debate about what broadhead design is best, fixed blade or mechanical. Both will definitely kill a bird if placed strategically, so the choice is often a personal one, but there are pros and cons to each when it comes to hunting turkeys.

There’s no doubt that the low-profile fixed broadheads commonly used on deer will also kill turkeys. They are known for their strength and durability, cut through feathers with ease, demolish bones and are known for deep penetration. They are a good choice for hunters pulling low-draw-weight bows or when using light arrows — but pinpoint accuracy is a must. The reason is that their rather small cutting diameter greatly reduces the margin of error on less-than-perfect shots to the vitals. There are some two- and three-blade fixed broadheads available that provide a larger cutting area, although they can be difficult to tune with some bows.

For most turkey hunters, mechanical heads are the only way to go. Mechanical heads fly like a field point due to their low profile when closed, and although energy is lost when they open on impact, with today’s high-speed compound bows and crossbows, retaining enough energy to reach the vitals really isn’t an issue. Based on personal experience, pass-through shots are still a high probability.

The real advantage of mechanical broadheads is that their larger cutting diameters of up to 2 inches or more provide devastating wound channels and extensive internal damage and blood loss. Mechanical broadheads are also much more forgiving of marginal shots. They are not as durable as fixed heads — but just as deep penetration with today’s bows really isn’t a major issue on turkeys — neither is broadhead durability. Generally speaking, mechanical broadheads perform best when matched with heavy arrows, and are much easier to tune than fixed broadheads in case adjustments do need to be made.

With all things considered, an agreement can be made that the best broadhead in most cases is the one that each hunter knows best, has experience with and has confidence in. If it flies true, has always performed well, and if we are confident in our shooting ability, that might be the way to go. It is just that some broadheads, in this case mechanicals, offer a higher degree of devastation and level of forgiveness in the event the perfect shot is not made, which is always a possibility when it comes to bowhunting turkeys.

ANOTHER ALTERNATIVE

Despite the rather small size, a turkey’s vitals offer the best chance of a sure kill. Head and neck shots are another option, but in most hunting situations offer a low percentage of success with standard-size fixed or mechanical broadheads, especially beyond 35 yards or so. Hunters can increase the odds with one of the so-called guillotine broadheads that offer a 4-inch or more cutting diameter.

But head and neck shots are still a challenge even with these extra-large heads because a turkey’s head and neck rarely stop moving. In order to work best, a bird should be facing toward the shooter or to the side with the head and neck extended. In these positions a turkey’s eyes are always looking, putting the hunter at a disadvantage. Shots while the head and neck are in other positions might be a possibility depending on the situation, but the chances of success diminish considerably.

Another thing to consider is that the extra-large broadheads are not as aerodynamically stable as smaller fixed blades and nowhere near that of mechanical broadheads. So they don’t always fly perfectly from all bows, especially at long ranges. Compounds and crossbows need to be properly tuned to put these guillotine-style heads to ultimate use. Even then, the best shots are generally at 25 yards or less, and ideally the bird should be stationary. Meaning the hunter must be close and prepared to release when the opportunity is offered.

The other factor is that in order to kill a bird with a neck or head shot — it must be a perfect hit. A mere nick or skim in the head area without cutting a good part of it off, or to the neck without severing the spine, may result in wounding the bird and it running or even flying away.

It’s not all negative when considering using guillotine heads, so I’m not trying to say they shouldn’t be used. A turkey’s head and neck are much larger than the vitals, and within acceptable range and when a bow is shooting accurately, they’re easy to differentiate at acceptable shooting angles. The red head also provides a single focal aiming point, rather than a bunch of feathers that can obscure the vitals. And, when guillotine heads do their job as designed, they do it exceedingly well, dropping a bird dead on the spot.

When it’s all said and done, choose the broadhead that you have the most confidence with. In most situations that is the one that will work best. Just keep in mind, bowhunting turkeys is rarely easy and they can be tough to kill with an arrow. Some broadheads are specifically designed to provide an advantage. Don’t hesitate to use it.