Coyotes are among the biggest predators for wild turkeys, targeting everything from eggs in nests to adult birds they can capture.

Have you ever been close enough to a bobcat to see the yellow-brown pigment flecks in his irises? I’m talking about a wild, on-the-loose, free-roaming cat, not one with a foot hung in a trap. Well, I have, and I can tell you it’s an unnerving experience.

By Jim Spencer

It was long ago. Call it 1985. I was turkey hunting in the Ouachita Mountains of western Arkansas. The Ouachitas are rough, rocky and often steep. Not as rough, rocky and steep as much of the Rockies, granted, but it’s enough of all those things for me.

The turkey I was working had hung up on the other side of a patch of Volkswagen-sized chunk rock. He was only 60 yards away and obviously interested, but he was reluctant to come around the rockpile. I’d been on him for nearly an hour, and for most of that time we’d been occupying our positions on either side of the boulder field. It was time to move. When I turned my head to start gathering up my equipment, I was looking into the unblinking, vertically slitted eyes of a big tom bobcat, at a distance of about two feet.

At least, I think he was big. At that range, appearing unexpectedly like that, a half-grown Chihuahua would loom large. This thing looked as big as a jaguar.

But evidently I looked big and menacing, too, because the cat and I had almost identical reactions. He bounded down the slope and I scrambled up it, and by the time I got my wits back I was ten feet from my original position and had moved enough rock to start a small avalanche. Not surprisingly, I never heard the turkey again.

Not Uncommon

Calling in predators – not just bobcats, but also coyotes, foxes and even bigger stuff like cougars and black bears – isn’t that rare for spring turkey hunters. Fall turkey hunters, too, I suppose, at least those who don’t use dogs. My personal list includes that bobcat and several others, maybe three-dozen coyotes, a half-dozen gray foxes, two red foxes, one comical yearling black bear, and some oddball stuff I’ll tell you about in a minute. That’s the ones I’ve seen, you understand. As is no doubt the case with turkeys, I suspect I’ve called in far more predators that I didn’t see.

I’ve heard and read lots of stories about called-up predators from many other turkey hunters, too, a couple of them involving instances where the hunter was actually attacked by the stalking predator. One time the attacker was a cougar, another a coyote, and several were bobcats. The attacks were brief, with the critter breaking off as soon as it realized its mistake, but it doesn’t take long for a cougar or bobcat to hurt a fella, even if it’s by accident.

Hunting coyotes and bobcats along with an effective trapping program may give you a leg up on helping turkey populations thrive.

Similarities of the Hunt

None of this is in the least surprising, when you think about the similarities between predator hunting and turkey hunting: First, the target species is usually brought to the gun by calling, and while the psychology is different, the results are comparable. In turkey hunting, you’re making hen sounds to attract gobblers, but the predators are also attracted because they want to eat the hen rather than mate with her.

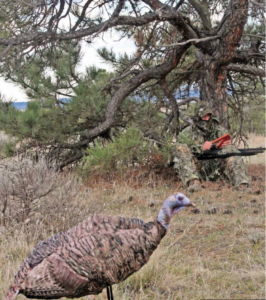

Second and third, the hunters are usually dressed in head-to-toe camo and are usually concealed in a sitting position, usually behind a blind or in front of a backdrop that breaks up their silhouette, or both. The purpose, of course, is to hide the hunters from the approaching target animal.

Finally, decoys are often used by both predator hunters and turkey hunters. Predator hunters usually use fur or fake rabbit decoys and turkey hunters usually use turkey-type decoys, but they are all designed to lure in the target animal and divert attention away from the hunter’s position of concealment.

All four of those similarities combine to make it not only possible but also likely that if a turkey hunter keeps at it long enough, he’ll eventually have some sort of encounter with four-footed, sharp-toothed wildlife. Sometimes it can turn into a rodeo.

Unexpected Encounters

For example, a buddy and I were turkey hunting in a western state about 15 years ago. It was late afternoon, shadows growing long. We were concealed in a brushy fencerow overlooking a pasture and calling fairly loudly, trying to make something gobble so we’d have a starting place the next morning. From beyond a similar brushy fencerow on the other side of the field we heard a coyote symphony break loose, the mated pair somehow managing to sound, as they always do, like a dozen choir mates were singing with them.

It was an enjoyable serenade, and sure enough it made our turkeys gobble, far away along a creek on the other side of the property. We were just sitting there enjoying the last few minutes of sunlight when the pair of coyotes broke through the opposite fencerow and came hell-for-leather across the pasture, directly at our position.

We were in a state that allowed killing coyotes in the spring, and the landowner had specifically asked us to do just that if the opportunity arose. They came on, running directly to where they’d heard the turkey calling, and at 25 yards the 3-1/2-inch loads of Hevishot efficiently did their job. The distant turkeys gobbled at our shots. The next morning we killed two of them as well.

Normally I don’t shoot the predators I call in while turkey hunting, because by that time of year (March, April or May) the fur is well past prime. Also, it generally messes up your hunt. I make exceptions when the landowner requests it, or when the animal I’ve called in is crippled, mangy or otherwise obviously incapacitated – which, in the case of coyotes in the East and South, is often the case. Several of the coyotes I’ve called in over the years haven’t had enough hair to make a bluebird nest.

But mostly, I’ve just enjoyed the unexpected encounters and kept my safety on. Some of them have been pretty comical. There was the Kentucky coyote that tried to bite my hard-bodied decoy. It was mid-morning, and I’d seen a gobbler in a pasture corner about noon the day before. About 10 o’clock, I slipped back there and set out a single feeding-position hen decoy and built myself a little hide 25 yards away in the edge of the woods.

I’d been there an hour, calling a little, when I caught movement out of the corner of my eye. A young coyote was slipping along the edge of the field. He got as close as possible to the decoy, and I could see his tail twitching with excitement as he gathered himself, paused a second to savor the moment, then launched in a blur of speed and motion.

Turkeys are quick, but if that decoy had been a real hen, I’m not sure she’d have been quick enough. The coyote came in directly behind and snapped at the decoy’s rounded back, and I heard his teeth impact first on the hard plastic – clunk! – and second on each other –click! – as his lower and upper jaws slammed together. The decoy squirted sideways off its stake and the coyote skidded to a halt six feet past the point of impact. He turned and looked at the fake, now laying on its side in the short grass, and the cant of his head and the set of his ears reminded me of that spotted dog looking into the gramophone in the old Victor Victrola talking machine ads. (Google it, you young folks.)

The coyote finally walked slowly off across the pasture, occasionally looking back over his shoulder at the hen that didn’t play fair.

One Kansas afternoon I was trying to get the drop on a couple of longbeards I spotted catching grasshoppers in a pasture. I thought I knew where they would leave the field, and I was working my way around to the spot when I spied a big dog coyote in the field with the turkeys. He chased them around like a puppy, making half-hearted runs at first one gobbler and then the other, and it quickly became obvious nobody involved was very excited about it. Each gobbler in his turn would run a few steps, take to the air and fly 75 yards before setting down again. The coyote would then lope at the other gobbler, who would do the same thing. I watched them for 20 minutes, then went on to my ambush spot, and just before sundown both gobblers came walking along the edge of the field with the coyote trailing them 50 yards back. The coyote and one of the gobblers left there in a hurry.

I once called in a skunk while turkey hunting, but that time, stupidly, I did it on purpose. I was hunting open woods in Missouri and nothing was happening, and when I saw the skunk waddling by I decided to have some fun with it. Using my mouth call, I applied a lot of pressure to the reed and let out a couple mouse-like squeaks. Skunks are nearsighted, but they hear pretty good. This one stopped in his tracks, stuck his nose in the air and started sniffing the breeze. I squeaked again and here he came, quartering to the sound like a bird dog working a quail field. He got closer and I kept squeaking, and it wasn’t until he was well inside squirt-gun range when I remembered that he did indeed have a squirt gun, and it was loaded.

So I stopped calling, but he didn’t stop coming. At five feet I kicked at him a little with my foot, and he stopped then. But when his forward progress halted, his tail came up. Not good. I froze, and after a while the tail slowly lowered and he turned and ambled on off on his skunky business. I never tried that stunt again.

Several years later, I did more or less the same thing with a yearling bear in central Pennsylvania, but that time I was using hen calls instead of mouse squeaks. I saw him at 150 yards, and every time I called he came closer. When he was 20 feet away I simply stood up. So did he, but then he dropped back to all fours and strolled away, curiosity apparently satisfied.

Feathered Friends

Birds of prey have occasionally figured in misadventures with other critters on turkey hunts. I watched an immature bald eagle plummet out of the south Florida sky onto the unyielding back of a hen decoy one morning a couple years ago, setting into motion a circus that included a pair of nearby sandhill cranes getting all riled up, a chorus of aggravated purring from the four longbeards that had been approaching the decoys when the eagle attacked, a snappy double by my buddies who were sitting in the blind near the decoy, a thorough thrashing of the two downed gobblers by the two survivors, more excited chatter from the cranes, and finally a last shot that killed one of the remaining gobblers and sent the fourth one packing, with the eagle chasing him like a falcon after a sparrow. That was quite a show.

Another time a red-tailed hawk made a swoop at my wife Jill’s hard-bodied decoy. Jill said she was about half-asleep and looking at her feet when she heard the whump! and looked up to see the hawk and the decoy looking at one another across four feet of pasture. The hawk shook itself, walked in a dignified manner four feet farther from the decoy, and took off as if nothing had ever happened.

Then there was the Cooper’s hawk that actually lit on my gun barrel as I sat motionless on a wooded Tennessee hillside late one April morning. I’d been working a gobbler and he’d gone silent, and I was expecting his red head to pop up any second. I was making soft sounds, purrs and clucks, with a diaphragm, and I was laser-focused on the edge of the rise out front where I expected the gobbler to show. When that hawk came in his left wing grazed my right ear, and he would have settled onto the gun barrel for a perch if I hadn’t jumped like somebody had hit me with a cattle prod. He sure was pretty for about a third of a second, though.

And I suppose it doesn’t really count as a predator call-in – at least not in the conventional sense we’ve been talking about here – but I once had a barred owl snatch the hat off my head on a turkey hunt. I’d been owling to try to get a bird to gobble, but instead I called up a pair of owls. They sat in trees above me and really gave me a cussing, and after giving it back to them for a while I turned to walk away and resume my hunt. When the owl took the hat off my head he got a little scalp as well, and it nearly knocked me down.

I’d like to claim innocence here, since owls are protected and I’m basically a law-abiding citizen.

But I can’t, and I’m out of room here anyway, so I’ll say nothing further about this particular incident except to tell you I still have the hat.

Jim Spencer of Arkansas is a veteran trapper, writer and diehard turkey hunter who has traveled throughout the United States pursuing gobblers and experiences.